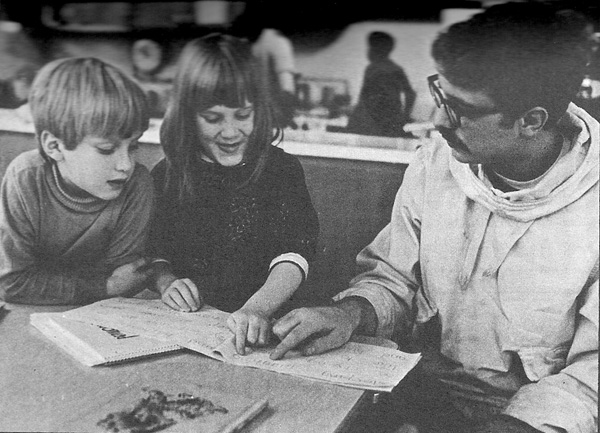

Bill Ayers and the Children’s Community (1968)

Bill Ayers

Bill Ayres is one of the founders of Children’s Community, an integrated school community in Ann Arbor, Michigan. He has since changed jobs and is now working full-time on various Ohio and Michigan campuses as an organizer for the Students for a Democratic Society.

Bill Ayers at the Children’s Community School before going underground as a fugitive

One of the major motivations for the people who started the school was that they felt there wasn’t a good model of an integrated school: the integrated schools were in many ways as racist as the old segregated model. We’re trying to approach integration in a totally new way. Not only do we have black and white kids in the same school, but we don’t make any value judgments about either of those groups of kids, because making value judgments turns out to be racist.

In every integrated school I’ve seen except ours the model for failure is everything that is ghetto or Negro culture. If you dress a certain way, prefer a certain kind of music or food, then you’re ignorant. It comes out most obviously in language. When a child says I ain’t and the teacher says it’s wrong, he’s destroying a lot. The child grew up saying that. His parents speak that way, everyone he knows speaks that way, he’s learned to speak his way successfully and suddenly he’s confronted with a new system that says he’s ignorant.

In this way the integrated school may be more destructive to both white and negro kids than the old segregated system.

What we try to do is to allow these groups of kids to learn from each other, to exchange things, throw things away, pick things up, without any kind of value judgments. I think that more than anything it is dangerous to consciously create models for kids to emulate. Most of us have had the experience of a model of what a teacher was and what an adult was, and we found that model, especially as we got older, a very restricting model. When you were sixteen the model didn’t screw, didn’t drink and didn’t mess around and those were all things that you wanted to do, so that the model was unrealistic. Of course we found out later that it was just a model and not true at all. One of the advantages of a school like this is that kids aren’t forced to believe in one kind of model: there are a lot of models. The group of people that comes into the school is in a lot of ways very diverse.

There are students who come in, community people with all kinds of different ideas about politics, life styles, kids, interests. Kids can learn much more from a number of different models. Everyone says, for instance, that the model of a nice cop is unrealistic for ghetto kids because cops are just not nice in ghettos.

We get out of the community a lot by taking trips – as many as five or six trips in a day – and the vital sense you develop in the community of what to expect from different adults gets tested out. You learn that some cops are nice and help you across the street and others aren’t so nice. I think they are getting a much more realistic picture of the world. The point is that kids learn by testing reality and not by what someone has decided is the truth they are going to tell them.

Picked things up and threw things out

I don’t think you can generalize from twenty-five kids in three years, but I think we have seen some indications that this is a good approach. We’ve seen every kid come in much narrower than he is today. The white kids came in generally quieter, more academically oriented, more afraid of new situations. The Negro kids came in busting out all over with enthusiasm, excitement, violent play. They enjoyed new situations, meeting strangers; they liked exploring, and of course they spoke differently from the white classmates. We’ve seen in three years that the white kids have loosened up a good deal, that they now follow the lead of their black classmates; they too explore on a trip, they go off by themselves and ask questions of strangers and kind of snoop around. They do more physical kinds of play, they dance much looser, they’ve picked up some of the language and thrown some away. The Negro kids today are able to spend a lot more time doing something quiet, they’ve picked up some of the language of their white classmates. We’ve seen this exchange completely without our intervention, without us saying these things are good or bad, but just by themselves they have picked things up and thrown things out however they saw it necessary.

The ratio of black and white kids in the school is about half and half. We make decisions when we accept parents of kids to keep a lot of different balances -age balances, sexual balances, race balances – so that in different age groupings there are different kids. Each kid has kids his own age and his own colour and sex to play with. It’s really hard to do when you only have twenty-five kids – like programming on a computer.

One of the problems is that the school is, in a lot of ways, much more oriented towards black kids, or rather the atmosphere that prevails is created by those kids in the sense that many of the things that go on there are dominated by black kids, We didn’t consciously make that decision, but the fact is that the black kids are more of a group, they are older and smarter. The black kids have been in school longer as a group. They tend to be more open and more anxious to get out of their houses and hang around with us. Some of that was certainly conscious. We live in a black neighborhood now. We thought it would be good to be near those kids, because we have been in a white neighborhood before and much nearer to most of the white kids.

Another problem is that we do not have any black staff. That is primarily because we can’t afford to pay anybody and there are very few people at the university that are willing to devote time to the Children’s Community rather than get a college degree and a job. That is something that really works against us. Parents come, and are encouraged to come as much as they can, but that is never regular because they have to work. The first year we had an unemployed black guy who came regularly and we now have a black girl who comes once a week, but it is still one of the big shortcomings.

There is no conflict between black and white kids in the school. There is real openness and acceptance of other kids. But there is a kind of ghetto atmosphere in the school. It is a poor run-down place to begin with and much noisier than it would be if we had all white kids. Yet that is not a simple matter of class difference. We have wealthy kids who are black and white, and poor kids who are black and white, The spectrum of the school runs from very poor people who can’t afford to pay any tuition to people who are professors and make over $10,000 a year. I think the wealthiest kid in the school is black, but he is about the only one that crosses the economic boundaries. For the most part the black kids are poor. The fact is that the white kids who are poor are the sons and daughters of struggling students or new left parents coming out of a middle class culture. And the black kids whose parents may make more money than those people are still coming out of a ghetto culture. It is hard to talk about the differences economically.

The economic and racial differences between kids are sometimes reflected in the kids’ attitudes to each other. When they leave the school, the white kids probably go to their white neighborhoods and the black kids go to their black neighborhoods. But they play together outside of school more than kids from most schools, although not necessarily inter-racially. Given the fact that they are scattered all over Ann Arbor, for Todd to play with Duke is a big trip, and yet they do it three, four, five times a week. More important than the inter-racial relationships that are formed (which, after all, are hard to measure) is the fact that exchanges take place in a very free atmosphere that is broadening for all of them.

On the outside

We see learning as going on every place – unstructured and undefined. When we talk about the discovery approach to learning, or about making learning a total process, we often talk about the cooking we do and the trips we take. We take trips every day certainly. That doesn’t mean every kid, but those who are interested in whatever is happening. Sometimes the kids suggest a trip, sometimes we do. If we have to plan it we involve the kids in the planning. We don’t consider the teacher suggesting a trip a betrayal of the discovery method. If there is a healthy open relationship the kids feel no kind of pressure about accepting the suggestion or rejecting it. Whether they want to go or not has nothing to do with what the teacher thinks of them. We do think that we have a responsibility to make a lot of different kinds of things accessible when available, and that includes materials, trips, even activities we might bring in. For instance, I was reading a book to three kids about fossils, and I discovered through reading that you could find fossils in limestone. Since limestone is plentiful and commonly used in a lot of the buildings around, I suggested a trip to go to the administration building and look at the marble floors and the walls to find the fossils. We did it. It was the kind of thing I could suggest to tie into what they were doing.

Apples, hamburgers, cars and airplanes

A number of times we’ve gone to an apple orchard and eaten the apples. Once as we were leaving, a truck was loading up with apples. One of the kids wanted to follow it and we did. It dropped off a load of apples at the A & P and we went in and bought some more apples to eat. You could see in that whole process that a real understanding about the economics of apples was starting. Apples are grown, sold, and bought.

Another trip came out of a discussion of meat. Someone in the group said wisely that hotdogs come from a cow you know. Someone else added that hamburgers come from a cow too. I sensed in the discussion that they were fascinated, but didn’t have a clear understanding of what they were saying. Everyone knows that meat comes in pieces and packages. When someone asked if it was true that salami comes from a sheep I started to talk about it. I said it was true that meat comes from animals and that we kill a lot of animals every day to get the meat we need. This was very fascinating to them. We talked about going to Detroit to see them slaughter animals. I arranged the trip and took five kids. The only stomach that turned was mine. We spent a couple of hours watching them herd in pigs, electrocute them, slit their throats, hang them up, take them down, cut them up, and package them. The way they talked about it afterwards to their friends and to one another was significantly different from what they had said before. I don’t think there is any way this kind of understanding could have been gained through lectures, pictures or adult pronouncements. Perhaps we ought to record some of the discussions, but I would argue that written records are a sort of neurosis of older people, who want to get the understanding spelled out on paper.

Oh yes, I just remembered another great trip. There’s a real fascination with cars with a lot of little kids, you know. Interest in cars can lead to any number of things but a couple of kids really wanted to see the way a car was built so we arranged two trips – one to the Cadillac plant in Detroit (of course being near Detroit helps) and one to the largest Ford plant. An interesting thing happened, I think. You see the way I learned about automobiles was through the history of automobiles and Henry Ford and all that, and Henry Ford was a genius and he did a lot of good for the whole country and he liberated masses of people with his invention. Now as I got older I started to get a different analysis, and I feel that Henry Ford did more to enslave workers than he did to liberate them. But you know my philosophy of teaching overrides both of these views, and I don’t think it’s wise to put either one of these on kids – to tell them that Henry Ford was a genius and liberator nor to tell them that he was an enslaver.

So what we did was go to the plant. Coming back from the Cadillac plant I had about five kids in the car, I think, and they were concerned with different things. Some of them were concerned with how amazing it was and it was amazing to watch the assembly line, it’s an amazing kind of thing if that is what you want to see. It’s a stroke of genius in a sense to see that all this can come together and make a car – so some of the kids were concerned with this. Another group of the kids were talking about the fact that it stank, that it was noisy, that it was filthy, that it was too long, that the trip was too long, it was boring…

Okay, so without me imposing my values on them, or someone else imposing theirs on him, they learned what they wanted to learn and I think that they learned it much more significantly than if we had given them all the lectures about it. You know, in a sense, this says that any kind of social studies that you could possibly teach or write books about has to be alive, in a sense has to be incomplete at least and the point that is often made that these kids know more about sociology and about social sciences than we do – if by social sciences we mean the make-up of society and how one exists in it – that is true.

So I think the car trips were fascinating to us. The airport trips are other ones – kids love airplanes, they all love airplanes but about five or six love them more than others, so there was a while there when we were making about four or five trips to the Metropolitan Airport a week which was getting a little heavy on the trips because he is only one person and the children need a capable adult to control them should consider that classes are going to get bigger and that you can’t control 35 kids unless you spend your time bringing kids back into the group. The only possible solution is to let kids do what they are interested in. You’ve got to trust them to go off into many different activities at the same time. The student staff ratio is a big bogie. Successful public school teachers in this country have come to the decentralization of the class through trial and error. They learned that any other way their primary role was as cop, their secondary role was bureaucrat and lastly they might be able to get a little bit of teaching done, though they weren’t even sure of that.

Using what is there

Cooking is another of our activities that allows a wide range of learning. Through cooking you have to get to things like reading in its natural setting, and some kinds of chemistry. You can very easily go into social sciences. If one kid makes cheese sandwiches one day, another kid might bring in his mother’s recipe for corn bread and chitters, and you get a whole discussion about cultures. You have to allow food to be used in a lot of different ways, to be messed with, to be thrown around some, used as a weapon, to be played with. Cooking happens all the time. There is always someone in the kitchen, usually a few kids. They love to cook. They come with baloney sandwiches and they fry their baloney before they eat it. They use whatever is there.

Bombarded by words

With all the hysteria about reading, we find that kids learn to read in a million different ways. Some learn to read because they like cars and want to learn the different names of cars. Others learn because they go on a lot of trips and read the signs along the way, they learn to read each other’s names, or they read the labels in a store, or they learn to read because they like to. Most of the kids really do want to learn to read. They learn to talk because everyone around them talks. They want to be competent. They want to make sense out of things like everyone else seems to be able to do, so they learn to talk, and the same is true of reading. It is impossible to exist in this world without being bombarded by words on television, street signs, advertising. Kevin, for instance, learned words like Dristan and Stop. Michael learned words like synagogue. These aren’t the clean clinically-tested sociological words.

Part of the great sorting-out process of American public education is that a lot of the kids who come through high school don’t know how to read. In this sense the school system has failed because it has set itself up as the institution that teaches reading. It really ends up in just teaching a skill, and we are not particularly interested in that. We hope that the kids can do more than identify certain words. We hope they learn how to express themselves, that words have a certain power, and the only way to learn this is to have something powerful to communicate and then to have the opportunity. Learning just can’t take place in a situation where you have curriculum guides and authoritarian teachers putting a mass of knowledge into an average student. That isn’t real learning at all.

How limits are learned

We have not sat down and decided what is important for kids to do. They choose what they do and they do what they are interested in. There is no set of values by which we judge cutting up carrots as opposed to doing something else. The kids are already fairly conscious of what is reasonable in relating to society and what is not. They are used to having their hands slapped. But I think they learn more in this kind of environment. What they learn about fighting, for instance, is infinitely more valuable than being told it is not nice to hit. Here they learn over a period of time and a number of experiences. Every day a kid named Kevin would pick a fight with Darlene and always get his ass kicked. There was nothing you could say to him to convince him that fighting with Darlene particularly was going to lead to getting your ass kicked. Over a two week period it finally sunk in. He learned he was better off not to pick fights with Darlene.

Another issue we had was swearing. We didn’t want to say swearing was wrong-probably because that’s phony, but also because we wanted the kids to learn for themselves what is appropriate. I always used to say when we were going on a trip that there was a good chance we would get kicked out if there was swearing. One day we went out to a printing place, and I told Jonathan that if he swore there was a good chance we’d all be kicked out. We walked in and he looked at the lady and said, You’re a mother-fucker’ and we got kicked out. I think he learned from that.

The school has always been in the basement of a church but the kids have been quick to learn the restrictions made by being in someone else’s facilities. The main restriction is that we have two not very big rooms. It is difficult to be able to be alone. But we have arrived at an arrangement through a meeting with the kids.

You have got to understand that meetings with six or seven year olds are just the most beautiful things. They last about a minute and a half, with everyone very excited, all trying to get in at once. They decided that the big room should be a place where they could ride tricycles and run up and down and play games like frozen tag and so on, and the little room should be crowded with activities like mathematical games, typewriters, books and art supplies. The little room is very crowded, but a lot of kids spend a lot of time there. This is the closest we have been able to get to a kind of privacy. Occasionally a child will ask to be by himself in a room we can use upstairs very quietly, or one will ask to take a walk with an assistant as a way of being alone. But the last thing on their mind is a nap.

Anxieties from outside

There are a lot of problems with trying to run a school like this, and one of them is the anxiety the kids feel from their older brothers and sisters, from the neighborhood kids about being in a different kind of school. They have a hard time seeing it as a real school.

The kids on their block talk about reading lessons, homework, and other things they don’t have. Kids shouldn’t be faced with the problem of having to defend their school. They should just think that they go to a different school, no better or worse. They don’t really understand the differences, and having to defend it simply confuses them. Parents send their kids to the school for all kinds of reasons. They are not all absolutely committed to our philosophy of education, and though we interview them carefully, I don’t think we always know whether they think it makes sense. The black parents as a group are fairly authoritarian with their kids. One of the overriding reasons they send them to our school is that they think black kids get a fair shake here, and they wouldn’t at another school. We try to avoid being used for kids who are found emotionally disturbed at the public schools. Although the whole philosophy sounds beautiful, when you actually have to deal with all the things that come out in a free atmosphere it’s not always pretty. A lot of anger and hostility come out and are allowed to be expressed without retaliation.

The kids have a tremendous identification with the school as a community. There is the sense that it is our school. I think that if we continue to grow at the rate of a grade a year, if we get through junior high, we will have done a great deal. The kids who leave then will be able to make conscious decisions about when they will or won’t play the game. People often ask how kids adjust if they have to go to public schools. When you think of what that means, it means doing everything for the approval of the teacher, moulding oneself around what other people expect.

It’s a double-edged knife. The kids who don’t adjust get screwed in one way, but the kids who do are just getting moulded into that other-directed person. It’s a shame.

Funds and state boards

I think that the majority of our problems would be wiped away if we had an angel come along with funds. A year ago we had the major problem of not having a full staff. Now the staff is full and working well together. If we had our own building and the kind of supplies we need it would be golden. We urge other people – groups of parents, community organizing projects – to start their own schools too. We could get some information together about how we got supplies, raised money and coped with the legal hassles.

We have no enemies now because there is really nobody around who cares a whole lot about what we are doing. At some point when the school becomes more threatening to different groups I can envision a legal hassle. There are a lot of legal things that hang over our heads but have not yet come down. Teacher certification is one. Now we have one certified teacher in a room, and as far as the State Board of Education is concerned she is the only one who is supposed to engage in any kind of learning situation with kids.

Everyone is counter to having adults in the classroom and to using the resources of the community. One of the funniest things the administrators or the State Board talked about was the reason we needed an accredited teacher. An accredited teacher is the only one who can make learning decisions. We talked about that. I said, Well, we have a retired engineer who comes in and does science experiments, is that all right? And he said, Yes, that’s perfectly fine as long as he does not make learning decisions. Then we have a lady who comes in and dances with the kids. Is that all right? That’s demonstration of a skill, as long as the demonstration of the skill is not a learning decision. It became clear that that term just defined itself. We asked about the university students who come in one or two days a week, and they said that as long as the teacher makes the learning decision the assistant can sit down and supervise – as if from that point nothing about learning goes on. I have an idea that the children make more of the decisions than anyone else.

Teach black kids karate?

Part of what kids learn in this kind of situation is that adults are different, that they’re not always men, not always black, not always white. They don’t all blow their tops at the same thing. Some of them never blow their tops. Some of them would never like to sit down and read a story; some of them would never like to go on a hike. That’s all good to learn. Rather than confusing the kids, I think it sharpens them.

One of our primary considerations is to fight the monolithic system of American society. We still have the goal that people break out of their ghettos, that they grow and pull in other things. Our model of integration says that there are differences, and you don’t have to make judgments about those differences. When black kids are bussed into white schools, you have to ask, What does it mean for a black kid to ride through the ghetto to the suburbs? I think it is more damaging to him than when he just existed in his little ghetto school. It says that white schools are better, and white kids have learned better things. America is in a time of crisis and we don’t know what kind of society these children will have to ‘live in. But we’re not retreatist. Someone argued with me that if you want to prepare black kids for what is coming then you teach them karate, you twist them up and make them hate you. But my feeling is that when you give kids self-confidence, when you create an environment where they can learn who they are and develop a certain amount of pride, and where they can learn about the world in a very realistic sense, then no matter what happens in ten years, they’ll be ready. They’ll have more of a sense of what’s happening in our society than other kids. You don’t teach people to deal with difficult situations by punishing them. The kids have some positive ideas about what life can be like, and that’s the important thing. That’s why you can be involved in this school and find it regenerating for you day by day.

Teaching black kids

I think the original issue is still the issue: is this society going to educate black children or not. When it took the form of bussing, of Head Start programs, a lot of people got off. Now you see Black Power schools run by black communities. If you read the ’54 Supreme Court decisions you get a very clear sense of the whole concept of cultural deprivation before the words were even invented. What does culturally deprived really mean? The Negroes clearly have a very strong culture and it has had a tremendous influence on all of American culture. It doesn’t mean that their culture is isolated. The Coleman report says that of all classes taken together, the white middle class is the most isolated from other cultures in America. What culturally deprived ends up meaning is not suitable to this white middle-class culture. So integrated schools were pushed and pushed, and eventually, with the coming of the Coleman report, we realized that we had to confront the failure of integration and start to re-examine some of our assumptions.

Given America today, the reason you have a school like the Children’s Community is that kids are forced to go to schools, and why not provide the best possible school? Those of us who are running the school see in it a lot of political implications. We think that by creating this radical alternative and working with this small group of parents and kids in creating a model around which we can do other kinds of political activities, we can become a force for change, not just in schools, but in society in general.

You shaved off your moustache

Now I’m going to be running for the school board. Issues have to be raised, you know, like teacher certification, all the issues that could close us – they are really at the heart of what is wrong with American education, and you have to choose a time when you think you have enough support in the community and wherever you can get it, you have to last through a campaign where issues are raised like how you run a school, and you try to force some kind of change. As Skip Taube, one of our teachers, has pointed out: Either you are going to exist as an isolated wonderful little project or you are going to become a threat. Whenever you become a threat you are risking something but you waive that and you decide to risk that at some point and we have decided to do that now.

Running for the board can raise some questions that wouldn’t be asked otherwise. For example, people’s attitude to our school can raise some really fundamental things. For the most part the people in the education Establishment think that we are, you know, give us that patronizing stuff about nice idealistic kids trying to do a nice thing and under their breath they are all saying, Oh, it was tried forty years ago and found to be a failure. One was a dean in the Education school and we have argued with him for days, and after a lot of talking we of course realized that in fundamental ways we do differ. In fundamental ways he supports the status quo and in fundamental ways we are working for change. I saw him in the street today and he said Oh -with a couple of patronizing asides-and then he said, I see you have shaved off your mustache, and I said, Actually, I didn’t. It was shaved off in jail at Christmas by the police and I just haven’t had the energy to grow it back. And he said, Oh, I thought you shaved it off because you wanted to win. So obviously, he already knows about the campaign. . .

What happens is you have a bunch of nice people who push for reforms in the schools, the reforms are absorbed by the system and nothing fundamentally changes. Witness what happened to Dewey – that in a lot of ways all his rhetoric, a lot of the forms that he developed were taken into the public school system and yet nothing fundamentally was changed. But I think one of the interesting things about running a school like this is when you start talking to groups of people about the school and about free education generally and they start questioning what will happen.

I mean, is it possible to have a lot of Children’s Communities in this country? – and you start to throw that around. And what kind of kids will develop? and will they be able to fit into General Motors and a Ford plant? In evaluating questions like these, people may start to move, politically at least in their heads. Because it is clear that the school system that now exists does a pretty good job of channeling people into different places, of fitting kids for the Ford factory and other kids for the executive offices, other kids for politics, and academics, whereas our system doesn’t do that at all. Our system has, in that sense, a lot of very revolutionary implications because American society couldn’t exist with a lot of Childrens’ Communities, or said the other way, a lot of Childrens’ Communities couldn’t exist in America.

So around the issue of education, around the issue of what is a good way to treat kids, you can start to raise a lot of the issues about American society and why the political scene is the way it is. I have seen it happen a lot of times in classes, in groups – just that kind of progression, and that is kind of exciting.

Editor’s Note:

I saw Bill again in August and talked to him on the phone in early October. Since he made the tape, he ran for the board and was not elected. He feels it was worth it anyway, partly for the reason he gave in the interview – in public meetings he felt that by holding firmly to his radical position, the other candidates and the audience were forced to be serious about fundamental questions. Even more, he says it was worth having the chance to do some organizing of Ann Arbor high school students and teachers.

Recently he and two other teachers at the school, Diana Oughton and Skip Taube, took part in the Chicago demonstration. He and Skip were both arrested and their trial is pending. To be young in Chicago was to be a nigger, he says. He tells of one incident when he tried to get into a hotel but was stopped by police. A handsome McCarthy kid, well-dressed, came along and asked to go in and the police were about to let him. The kid grabbed Bill by the arm and said he’s my friend – we’re both going in and immediately the handsome guy became a nigger too and both of us were kept out.

Bill has changed jobs. He is no longer at the Children’s Community but is working full-time on various Ohio and Michigan campuses as a regional traveler for the Students for a Democratic Society. He says that for a year now, as the students have become more mobilized, he has questioned whether the school community in Ann Arbor was making the impact on society at large that it should. Apart from vague vibrations now and then and my running for the Board, I feel we have been too isolated, he told me. Schools like ours are still very important, especially as student revolt gets nearer to being successful, but I think I can be most helpful more directly as an organizer.

Eventually if there’s to be a serious revolution in this country there must be an adult movement, possibly built around professions like teaching. But any such movement must be built on the foundation of the student movement. In building this movement, one serious question we’re going to be facing ~ since the country as a whole is moving more and more to the right – is to choose when we must do things which are good for the movement which in the short-run are bad for the country. Chicago, for example, drove the country towards Wallace, but it built up the movement. Lots of unpleasant choices will have to be made.

The Children’s Community is in trouble right now. The fire marshal and the building inspector have said that we can’t meet any longer in temporary quarters and we don’t have the money to buy a building. The school authorities aren’t too pleased about this either but they aren’t pushing us. It looks as if we may not be able to open this year.

Source: About Schools Fall 1968

Ed. Note (1970): The school was finally closed down by the authorities, snuffed out by bureaucrats just as Eric Mann’s proposed Newark Community School had been earlier. Bill and Eric and Diana joined The Weathermen. Eric is in prison; Diana was killed in the bomb accident on W. 11th St; in New York; Bill has disappeared.

Last Editor’s Note (10/2008): Bill Ayers has become a huge controversial figure due to his minimal association with Barack Obama, who at this moment is a candidate for President of the United States. If you read this article, you can see that both Bill Ayers and Barack Obama have a big focus on education, especially the education of minority students.

As of this writing Bill Ayers is now a Distinguished Professor at the College of Education at the University of Illinois at Chicago. All charges against him and his wife were dropped due to the government’s ILLEGAL spying via COINTELPRO. So even though Bill was involved in bombing the Pentagon, the US Capitol building and NYC Police Headquarters, he had all charges dismissed!

Bill’s book, Fugitive Days: A Memoir, was published on Sept 10th 2001, one day before the World Trade Center attack. In his book he describes his days on the run, living in the underground world.

Posted by: skip

Views: 17442

Topic:1